Farmers' woes

Agriculture is one of the primary employers of people in India. According to a report by Niti Aayog, around 45.6 per cent of the labour force is involved in the agriculture sector, demonstrating the sector's importance for the country. As India still identifies itself as an agrarian nation, the sector and its labour force hold immense importance.

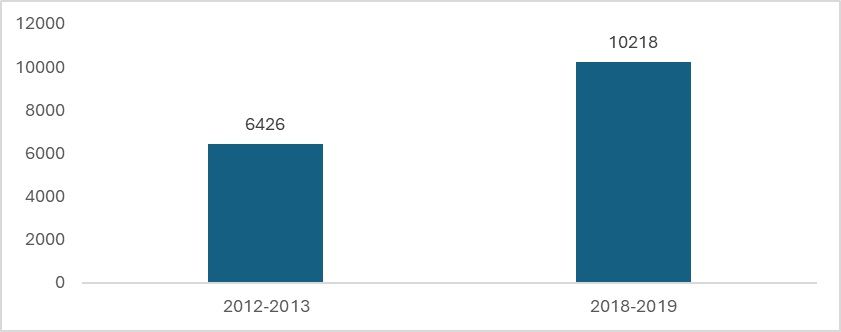

Farmers in the country are highly affected by weather changes and market prices. They are constantly under pressure due to lower incomes and prices for their crops that are lower than market rates. According to the ‘Situation Assessment Survey’ conducted by National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), the monthly income of farmers can be as low as ₹10,218. Therefore, the government must provide support to the farmers. However, this support itself may worry WTO members and could harm India’s global position.

Figure 1: Monthly income of farmers (in ₹):

Source: Situation Assessment Survey, NSSO

MSP, legalisation and WTO

The government of India establishes an MSP, which functions as a price floor for agricultural products. When farmers sell their produce, it is technically not permissible for buyers to purchase it at a price below the MSP. However, currently, the MSP is not mandatory for private sector acquisition of crops and is only enforced by government agencies.

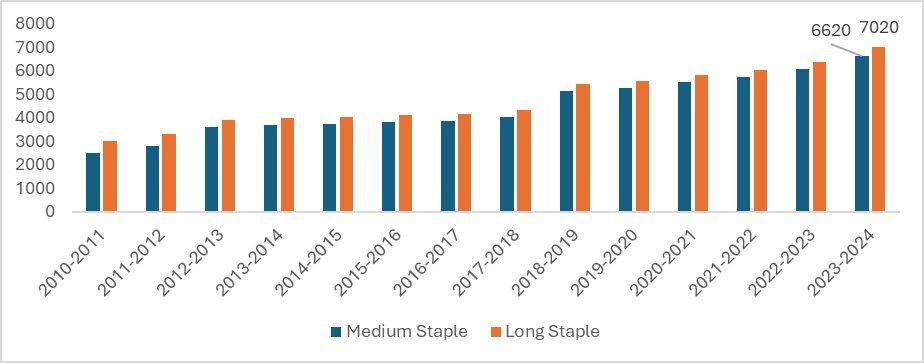

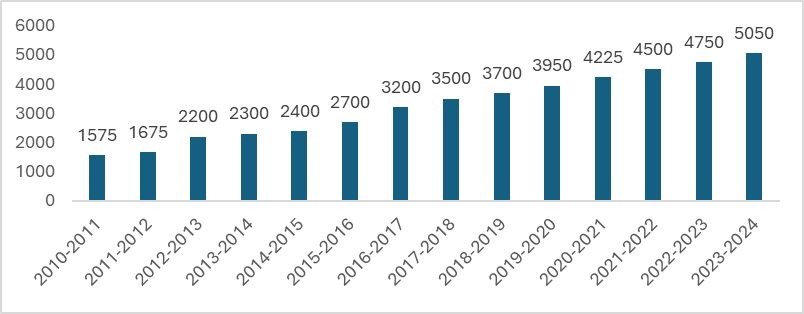

The implementation of the MSP is aimed at ensuring that farmers receive fair prices for their produce and are not exploited by market forces. The primary intention of the Indian government in implementing the MSP is to secure financial stability for the agriculture sector, which is one of the main employers in the country. Regarding the textile sector, two crops are significant: cotton and jute. Both have MSPs allocated by the government, which have been increasing annually.

Figure 2: MSP for Cotton across the years (In Rs/quintal):

Source: Farmer.gov

The long-term economics of MSP

India harbours a long-term perspective behind providing such price support: to stimulate increased production. As production expands, the country can eventually achieve economies of scale. India possesses natural endowments ideal for cultivating various agricultural produce, and providing price support can incentivise further production.

As the country attains economies of scale in the long term, it can also transition naturally into becoming a leader in both domestic and international markets. Establishing a legalised price floor across the market can enhance predictability and facilitate better financial planning. This can contribute to partially stabilising markets, which are often susceptible to fluctuations due to weather changes.

Cotton, for instance, is not only impacted by weather fluctuations but also by economic conditions within the country and in the international market. Hence, establishing a guaranteed price floor ensures minimum support for improved planning by farmers and enhanced predictability for the markets, thus bolstering the value chain. Figure 2 illustrates the MSP for cotton over the years. A similar case applies to jute, another product in which India specialises. Therefore, it becomes crucial to provide MSP.

Figure 3: MSP for Jute over the years

Source: Farmer.gov

The WTO twist

The primary reason why farmers are demanding an exit from the WTO is the nation’s inability to legalise the MSP due to the WTO norms in place. India became a member of the WTO in 1995, and since then, it is mandatory for the agrarian major to adhere to the principles and rules laid out by the WTO. However, not only India, but many developing nations face the same issue—the policies of the WTO become a hindrance in implementing any policies that can enhance the living standards of the people involved in the sector.

The same reason drives the farmers' demand for the nation to exit the WTO. The government struggles to ensure the legalisation of the MSP due to Article 14 of the organisation, which mandates bilateral and multilateral discussions with India’s trade partners to justify applications such as the implementation of a price floor in India's case. Furthermore, a sub-section of the article discourages the nations from applying subsidies or any other export support provisions (like MSP in the case of India) on the exports of primary products like agriculture. This particularly hinders India from making any commitments regarding the legalisation of the MSP.

The Uruguay Round, for example, is another issue that developing nations like India are calling for a review of. The amendments made in the round specifically categorised policies like the MSP as Amber Box measures that can distort trade and affect global market prices. Many different clauses are being proposed for negotiation by developing nations, but they are constantly being ignored.

There are certain methods for determining subsidies based on a standard formula provided by the WTO, known as the External Reference Price. However, the reference period dates back to 1986-1988, failing to account for even a one per cent inflation rate up to today. Therefore, the demands may appear reasonable from the perspective of all developing nations.

No FTAs

In addition to exiting the WTO, calling for a ban on all free trade agreements (FTAs) could significantly impact the nation's market access. India already has lower utilisation of FTAs, with some exceptions, and demanding their ban would be detrimental to the nation itself. This exacerbates the domestic challenges of de-globalisation. While nations like the EU and the US are also pursuing policies hinting at de-globalisation, there is a distinction here. The demands from developing nations to ban FTAs stem from unfair terms and conditions in the agreements, as well as from rules of origin and unfair tariff regulations.

Many FTAs, such as the potential US-India FTA and the India-EU FTA, raise concerns about being unfair to Indian farmers, which could worsen their conditions further. Therefore, opposition to FTAs is also growing. As of 2021-2022, India exports cotton to nearly 159 countries. Although very few FTAs have directly benefitted textile exports, it may be opportune to reconsider them.

What is the way out?

Although there are infrastructural and other issues involved, these particular clauses are the primary reasons why India is unable to promise any legalisation on the same. The protest to exit the WTO is not new in Asia; in the past, nations like Hong Kong and Indonesia have also seen protests erupt to urge their governments to exit the organisation.

The current farmers' protest comes at an interesting juncture—on February 26, there is a WTO meeting in Abu Dhabi where there is a chance that agricultural issues may be addressed. The entire Global South is looking towards India to raise the issue, given its past successes in the WTO. If the issue is at least discussed in the WTO—which was previously avoided by all developed nations due to their political issues—this will be a significant victory for India domestically.

ALCHEMPro News Desk (KL)

Receive daily prices and market insights straight to your inbox. Subscribe to AlchemPro Weekly!