The United States, along with the European Union (EU), is one of the leading importers of textiles and apparel globally. Over the past five years, there has been a notable shift away from reliance on China due to the implementation of the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (UFLPA). This legislation prohibits the entry of textile products suspected of utilising forced labour in cotton cultivation and textile production processes.

Anticipated consequences of this law included a decrease in Chinese imports to the US. While there has indeed been a significant reduction in Chinese imports, there has not been a substantial corresponding increase in imports from the Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) region.

The background

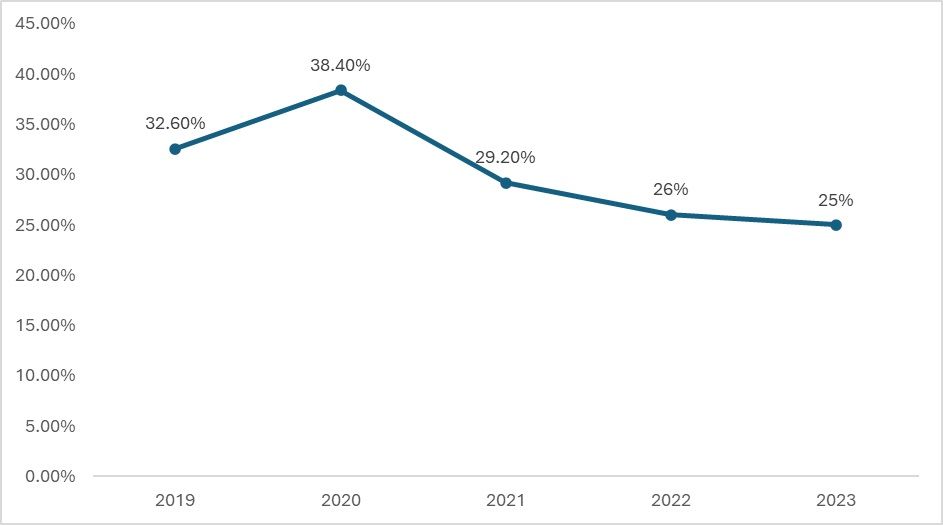

The share of Chinese imports in the US was highest at around 38 per cent in 2020. Beyond the allure of lower costs, the high demand for apparel imported from China was bolstered by the De Minimis law, which facilitated the duty-free entry of Chinese-origin products into the US. Significant import figures were recorded under this provision, exceeding $1 billion in 2023 alone, with Chinese fashion retail brands fully capitalising on this opportunity.

However, changes are on the horizon. Proposed amendments to the De Minimis Act include increasing the price ceiling, while more stringent regulations are being considered under the UFLPA. These regulations would mandate thorough inspections of apparel and textile imports to detect any presence of cotton or products derived from Chinese cotton.

These developments, coupled with the broader context of trade tensions and a growing sentiment towards reducing dependence on China, have led to a substantial reduction in the share of Chinese imports within the overall US textile import landscape.

Figure 1: China’s share in US’ total textile imports (in %)

Source: ITC Trade map

The share of Chinese textile imports in the US has notably declined to 25 per cent from a peak of approximately 38 per cent. Tariffs on Chinese textile materials vary, ranging from 0 per cent to 20 per cent. However, since 2020, an additional 15 per cent import tariff has been imposed on products imported from China, contributing to a significant decrease in their share. Despite these tariff adjustments, imports from other nations have not surged as anticipated.

Gradual shift

With Chinese exports experiencing a significant decline in the US import share, it was anticipated that imports from other nations would rise dramatically. However, the actual increase in imports from other countries has not met these expectations, raising the question: Can one truly detach from China? In today's interconnected world, detaching from Chinese imports appears nearly impossible.

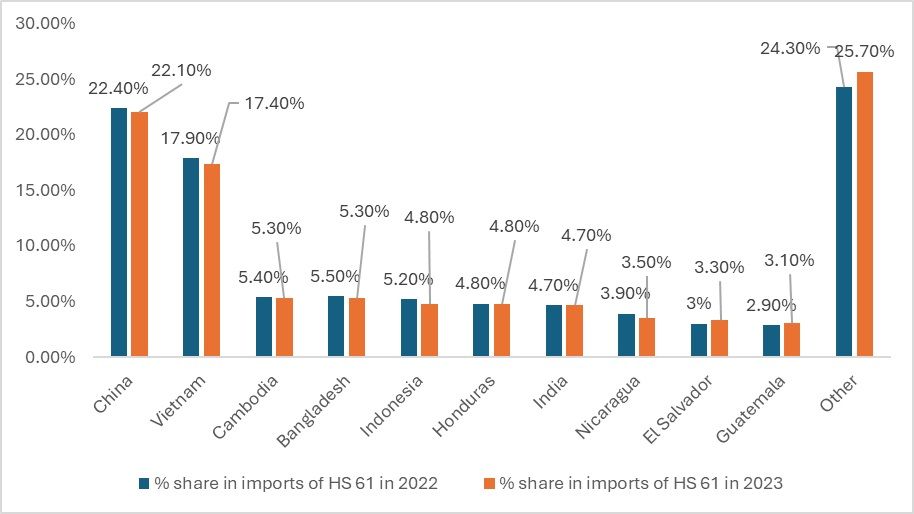

Figure 2: Share of different countries in US’ knitted apparel imports (HS 61) (in %)

Source: ITC Trade map

When examining the figures for knitted apparel, the share of Chinese imports has only slightly declined, from a peak of 22.40 per cent to 22.10 per cent. Conversely, Guatemala and El Salvador have experienced only marginal increases. Meanwhile, other nations have shown neither significant growth nor decline in their total share. Overall, import shares have remained relatively stagnant over the past two years.

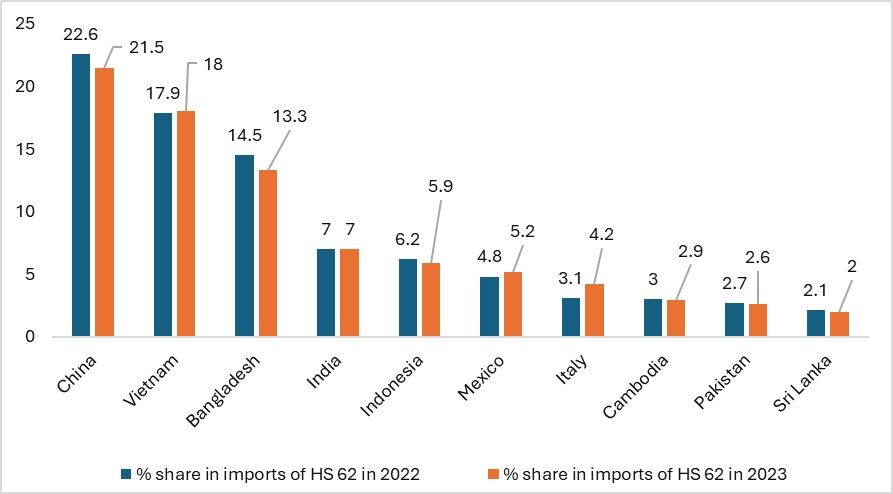

Figure 3: Share of different countries in US' woven apparel imports (HS 62) (in %)

Source: ITC Trademap

Even in woven apparel, the share of the imports from China is the same, whereas the imports from Vietnam, Nicaragua Guatemala, and El Salvador have seen a moderate increase in the import share. This shows the fact that the reduction in Chinese imports has either reduced to the maximum or there is something else behind the sluggish reduction in the per cent share.

Even in woven apparel, the share of imports from China remains unchanged, while imports from Vietnam, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and El Salvador have seen a moderate increase. This indicates that the reduction in Chinese imports has either reached its limit or there are other factors behind the slow decrease in their per cent share.

All is not clear

The primary reason for the reduction in imports from China, particularly in textiles and apparel, was the implementation of the UFLPA and the de-risking strategy from the nation. However, when examining the data on textile shipments rejected under the UFLPA, the figures tell a different story and may help explain why the total imports from China have remained stagnant. By looking at the total shipments rejected under the act, the situation becomes clearer.

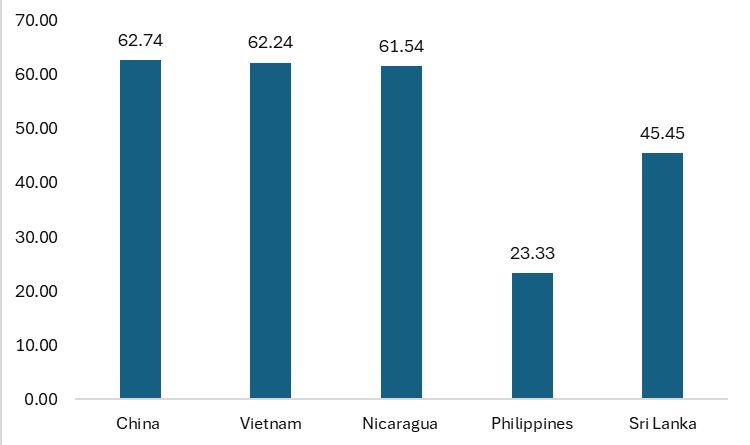

Figure 4: Textile shipments rejected from different countries under UFLPA (in %)

Source: US Customs and Border Projection (US CBP)

Besides China, Vietnam has emerged as a significant apparel exporter to the US. Notably, almost 62 per cent of textile and apparel shipments subject to UFLPA scrutiny were rejected, with both China and Vietnam leading this statistic. Another noteworthy nation, Nicaragua, which is part of the CAFTA-DR, also experienced a rejection rate of around 61.54 per cent. This could explain why total imports from CAFTA-DR nations haven't seen robust growth.

The US is actively seeking to reduce its reliance on China within the textile sector. The National Council of Textile Organizations (NCTO) recently proposed stricter measures against Chinese apparel and textiles entering the US via the De Minimis route. Consequently, imports sharply declined post-2020. However, since 2021, the reduction in import rates has plateaued, with the share of imports from other countries increasing at a sluggish pace.

Future Roles of UFLPA and possibilities

Reports indicate the presence of Xinjiang cotton in textile products exported from countries such as Mexico, Brazil, and Australia. According to the NCTO, these products testing positive for UFLPA-banned materials originate not only from China but also from other countries the US intends to rely on for textile exports. A significant concern arises from labelling discrepancies, potentially enabling these products to evade detection under UFLPA restrictions. This poses a substantial challenge to the effectiveness of such policies.

The US vehemently opposes the consumption of textile materials potentially linked to social injustices like forced labour. Therefore, initiatives like UFLPA aim to impose stricter regulations and propose traceability requirements for all textile products. However, the issue of ‘green labelling’, which indirectly involves banned Chinese products like cotton and cotton textiles in apparel from countries like Vietnam, Honduras, and Australia, contributes to the stagnation of import shares.

To address these challenges, efforts must focus on enhancing traceability for Chinese-related textile products, as well as studying value chains in other countries. However, it is essential to approach these issues carefully, considering the potential costs involved. Many policies aimed at restricting or reducing Chinese textile and garment imports in the US have yielded limited success thus far.

ALCHEMPro News Desk (KL)

Receive daily prices and market insights straight to your inbox. Subscribe to AlchemPro Weekly!