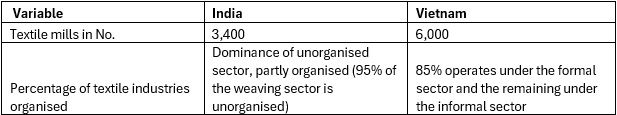

The Indian textile industry is one of the oldest in the world but remains one of the most unorganised sectors in the country. India is characterised by a predominance of informal industries, with limited enforcement of labour laws and minimal regulatory oversight of the sector's operations. According to the Labour Bureau, the overall unionisation rate in India is approximately 34 per cent. However, unionisation within the textile industry stands at only about 5 per cent. Unionisation of labour refers to the process by which workers in a trade, industry, or company organise to collectively represent their interests in negotiations with management over issues such as pay, benefits, and working conditions.

The textile industry in India continues to be largely informal, with ongoing issues such as forced labour, exacerbated by inadequate government regulation to protect workers from exploitation. A survey by Civicdep India highlights that, despite the existence of numerous legal protections, there is a significant lack of awareness about labour rights and the benefits available under these laws. Similarly, in countries like Vietnam, which have more developed labour regulations, textile workers face comparable challenges, illustrating that the mere existence of laws is insufficient to ensure fair and humane working conditions.

Textile industry scenario in India and Vietnam

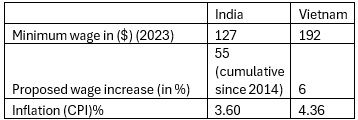

Table 1: Textile stats (2023)

Source: Statista, Invest India, VITAS, Femnet EV

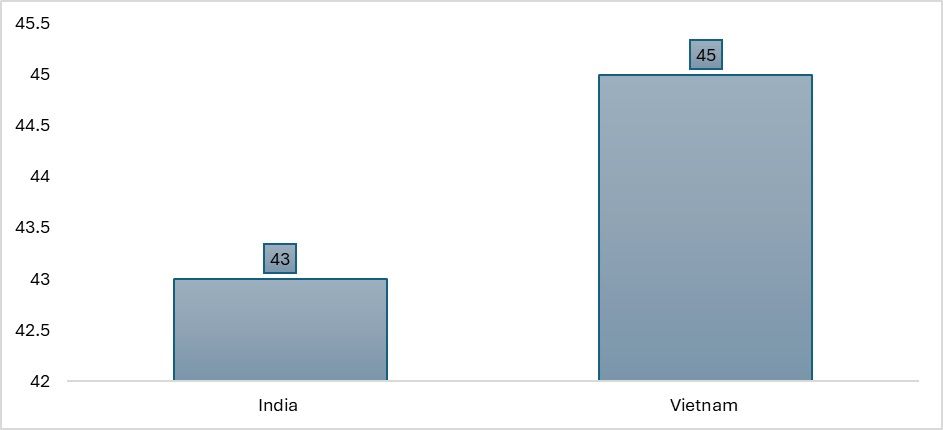

India and Vietnam are two of the world's leading textile-producing nations, both playing significant roles in exporting apparel to key markets such as the US, EU, and others globally. However, despite India's textile industry being larger in scale, approximately 80 per cent of its operations are within the informal sector. This high level of informality likely contributes to the lower unionisation rate in India's textile industry compared to other nations, where more formalised labour structures are in place.

Figure 1: Total employees and the rate of unionisation in Indian and Vietnamese textile industry

Source: Femnet, VITAS

Vietnam's textile industry is characterised by a high unionisation rate of 29 per cent and a predominantly formal sector, with 85 per cent of operations functioning within structured and regulated environments. This high level of organisation and workforce representation leads to better compliance with international standards, improved working conditions, and more efficient production processes. In contrast, India's textile sector is largely unorganised, with 95 per cent of the weaving industry operating informally, according to Niti Aayog, and only 5 per cent unionised, as reported by the Fair Wear Foundation. This fragmented structure results in weaker labour representation, challenges in regulation and quality control, and potentially poorer working conditions, making it difficult for India to achieve the same levels of efficiency and adherence to international standards seen in Vietnam’s more formalised industry.

However, both India and Vietnam face significant challenges related to labour unionisation and the overall efficiency of their textile industries. While Vietnam has established unions within the sector, they continue to face various difficulties. This highlights the broader issues impacting this highly labour-intensive sector in both countries.

Limited awareness, weak bargaining power

Research from TD Economics reveals a strong negative correlation between unionisation and wage growth. The findings suggest that sectors with higher unionisation rates tend to experience slower wage growth compared to those with lower unionisation rates. In Tiruppur's garment industry, a survey conducted by Civic Dep found that workers were sceptical about the effectiveness of unions in addressing labour issues, particularly wage negotiations. Furthermore, there is a troubling trend of employees being penalised or ostracised for participating in union activities. The constant threat of suspension or dismissal for joining unions has created a climate of fear, which has contributed to the low level of union participation in the textile industry.

Although many companies have labour unions, these often fail to secure fair wages for workers. In some states, garment workers are not even entitled to a minimum wage. For instance, in Tiruppur, the minimum wage has not been effectively revised since 2014, despite legal mandates requiring wage revisions every 10 years, and state laws stipulating wage adjustments every four years. Additionally, there is no specific legislation for apparel workers in Tamil Nadu, where the Tailoring Wage Act is applied to the garment sector.

A concerning trend has emerged where wages are deliberately kept low to boost competitiveness. According to IndustriALL, wages in the range of ₹9,000 (~$ 107.5) to ₹10,000 (~$ 119.17) per month are insufficient to meet basic living needs. Although the government has proposed an 8 per cent wage increase, no meaningful changes have been implemented by the industry. Furthermore, due to the industry's reliance on a largely contractual workforce, unionisation efforts have been hindered by high turnover rates. More than 80 per cent of workers leave their jobs, which hampers union efforts in the factories. Many significant changes affecting the industry have come from the Union government directly, with little active participation from unions in negotiations.

Vietnam

The challenges faced by Vietnam’s textile industry are similar to those in India, including high worker turnover and widespread gender-based discrimination. Vietnam has formally prohibited the formation of independent labour unions, allowing only state-controlled unions to operate. Although unionisation is present, many garment workers remain unaware of the role these unions play in labour welfare. While there are around 20 labour unions in the country, under previous labour laws, independent labour organisations were not permitted to engage in formal protests. As these unions are government-affiliated, they offer little to no negotiation for better wages, primarily serving as a channel for the government to communicate decisions to workers rather than advocating for labour rights or improved working conditions.

Research from a labour journal reveals that the textile and garment industries account for nearly half of all labour protests in Vietnam each year. The main driver of these protests is the inactivity of labour unions in negotiating fair minimum wages, prompting workers to organise informal protests. Recently, there was a legal mandate to increase wages in the garment sector by approximately 9 per cent. However, this decision was opposed by industry leaders, who argued that the wage hike does not align with the slower export growth, which may have decelerated in 2023.

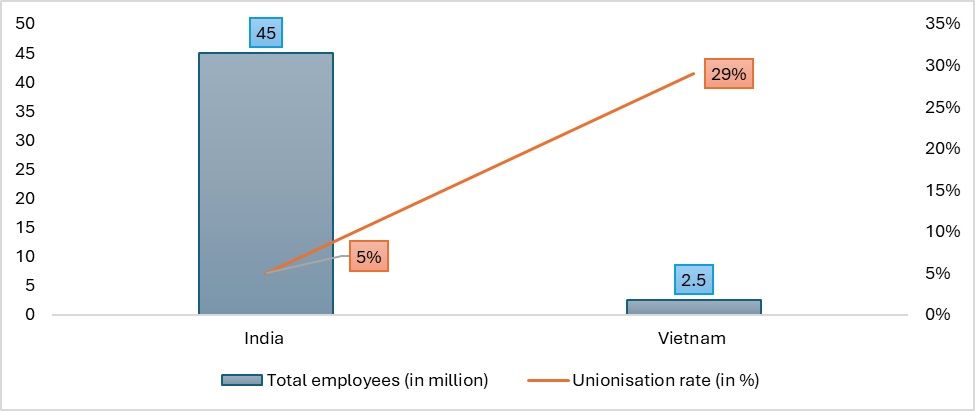

Working hours and overtime

Before moving to the unionisation of the textile workers, it is important to know the working conditions in the textile mills in India and Vietnam. The following table gives a clear overview of the working hours and the compensation for the overtime for the textile workers.

Figure 2: Working hours

Source: International Labour Organization (ILO)

Despite laws for regulating wages, overtime pay, and permissible working hours, the working conditions in the textile industries of both Vietnam and India remain far from satisfactory. According to research by the Anti-Slavery Organisation, Vietnamese workers face immense pressure to meet factory targets set by managers, often being forced to work beyond legal working hours. Although they receive compensation, the base pay for overtime is notably low, worsening the challenges faced by these workers. While Indian law mandates overtime pay at twice the regular wage, Vietnam offers comparatively less, requiring only 1.5 times the regular wage for overtime.

In India, although the legal limit for work hours is 9 hours per day, many workers end up working as long as 16 hours, often without proper overtime pay. To meet production targets, workers frequently exceed legal overtime limits, enduring long hours under harsh conditions. The lack of sufficient labour representation at the factory level in India allows such exploitation to go largely unnoticed.

Worker safety is also frequently compromised in both countries. Minimal protective equipment, such as masks or gloves, is often provided based on specific production tasks. In Vietnam, for example, if a worker suffers an accident on the job, factories typically cover only half of the medical expenses, and that too only upon request. In India, while compensation for injuries may be offered, there is no guarantee of paid leave for recovery.

To address these issues, less fragmentation in labour representation and the establishment of an effective mechanism to handle labour grievances are crucial. While unions exist in many sectors in both India and Vietnam, worker representation at the factory or mill level is almost non-existent, leaving labour issues unresolved and workers vulnerable to exploitation.

Common issues

Table 2: Basic economic profile of India and Vietnam

Source: Industriall, Business and Human Rights resource centre

Both India and Vietnam, despite having different levels of unionisation, face a common issue: the challenge of raising the minimum wage to match global standards. Regardless of the unionisation rates in these countries, the situation is largely similar. To attract foreign investment and maintain a supply of cheap labour, wages in both nations have remained stagnant. Even when wage increases occur, they are minimal and far below global wage standards. This stagnation has sparked protests in both countries at different times, leading to laws being passed to raise wages.

This wage stagnation persists despite local ownership of the majority of mills in India (95 per cent) and Vietnam (46 per cent). Surprisingly, even though Vietnam's textile industry is predominantly organised, a significant portion of workers operate in irregular or unclear employment arrangements. Meanwhile, India has the lowest proportion of salaried employees in the textile and garment sectors, as reported by the International Labour Organization (ILO).

When discussing sustainability factors like fair working conditions, it is crucial to consider issues such as the unionisation of labour, the bargaining power of workers, and government policies on minimum wages. These policies must account for the country’s inflation and overall economic conditions. Currently, the wages of garment workers in both countries are not in line with inflation rates. Although the structure of the textile industries in India and Vietnam differs, both countries share the common challenge of insufficient bargaining power among their workers.

Sustainability norms and labour laws

Sustainability regulations, particularly those outlined in the EU's Strategy for Sustainable Development and Circular Textiles, mandate fair working conditions for workers. Even before the introduction of sustainability laws, the European Union signed a free trade agreement with Vietnam, requiring reforms in Vietnam's labour laws. In addition, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) – which includes members like Australia, Mexico, Malaysia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Peru, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam – also mandates that member nations implement labour laws in accordance with the International Labour Organisation (ILO) standards on sustainability.

Figure 3: Textile exports of India and Vietnam (in $ bn) (2023)

Source: ITC Trademap

One of the key reasons for establishing stable labour laws is the rapid expansion of the textile industry. In India, the textile market is valued at $165 billion, and with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12 per cent, this growth demands labour laws that prioritise worker safety, provide stronger bargaining power, and empower unions to advocate for essential changes. However, India must consider both unions and informal sector employees when framing these regulations.

In 2020, India introduced a new labour code that raised concerns about labour security. The reforms include an easier "hire and fire" policy, allowing factories with fewer than 300 employees to lay off workers without state approval. While the aim was to simplify labour laws and attract foreign investment, this approach presents a complex challenge. Western manufacturers often seek cheap labour and relaxed labour laws, but their home countries demand goods be produced in nations with fair and ethical labour practices.

This creates a dilemma for countries like India and Vietnam, which must balance appeasing multinational firms seeking lower costs with meeting the ethical labour standards demanded by foreign governments. Protecting worker rights while maintaining the industry's global competitiveness has become a delicate balancing act.

As the global push for sustainability mandates the implementation of ethical labour practices in the textile and apparel sectors, greater coordination between governments and labour unions is essential. In India, however, there has been little dialogue between the government, planning authorities, and unions. While Indian labour unions are aware of sustainability issues and their importance in the value chain, they have been excluded from key decision-making processes and strategy development.

In contrast, Vietnam involves its central labour union in decision-making regarding sustainability and labour laws, though there remains a lack of awareness about sustainability-related initiatives. Many unions in Vietnam see these initiatives as part of the government's agenda rather than policies aimed at improving working conditions.

However, the pace of reforms in both countries has been slower than expected. Aligning with global standards requires a proactive approach from governments to protect labour rights, including the right to organise. Effective policymaking can only be achieved through proper collaboration between governments and labour unions. In India, this is particularly challenging due to the need to integrate both the informal and organised sectors into the policymaking process.

To ensure fairness, promote sustainability, and enhance worker welfare, greater collaboration between labour unions and governments is crucial. By fostering this cooperation, India can develop labour policies that protect workers, align with international standards, and support the long-term growth of the industry.

ALCHEMPro News Desk (KL)

Receive daily prices and market insights straight to your inbox. Subscribe to AlchemPro Weekly!